How the UNFCCC Can Tackle Fossil Fuel Subsidies at COP 28 and Beyond

The 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 28) presents a crucial opportunity to take stock of public financial flows to fossil fuels. Fourteen years after the G20 and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation countries made initial commitments to tackle “inefficient” fossil fuel subsidies, there is a major gap between governments’ rhetoric and action. In 2022, world governments provided a record USD 1.3 trillion in fossil fuel subsidies. This came despite the objective in Article 2.1(c) of the 2015 Paris Agreement of making “finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development” (p. 3).

Removing fossil fuel subsidies makes sense not only for accelerating climate action but also for broader economic and environmental reasons. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) finds that “removing fossil fuel subsidies would reduce emissions, improve public revenue and macroeconomic performance, and yield other environmental and sustainable development benefits” (p. 46). On climate mitigation specifically, the IPCC notes that “fossil fuel subsidy removal is projected … to reduce global CO2 emissions by 1–4%, and [greenhouse gas] emissions by up to 10% by 2030, varying across regions” (p. 46).

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is not the only international institution to address fossil fuel subsidies. International economic institutions, including the G20, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, International Monetary Fund, and World Trade Organization are also engaging with this issue, and subsidies are a target of one of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 12.c). Still, the UNFCCC plays an important part in strengthening global and national commitments, improving transparency, and providing space for dialogue and the sharing of experiences.

COP 28 in Dubai could be a turning point for action on fossil fuel subsidies—if there is political will. How have fossil fuel subsidies featured in UNFCCC negotiations so far? And how can action on fossil fuel subsidies be taken at COP 28 and beyond?

Fossil Fuel Subsidies and the UNFCCC: The story so far

Fossil fuel subsidies have received only limited attention in 3 decades of climate change negotiations, notwithstanding the tangible climate and development benefits of addressing them, as well as several attempts by individual countries to put the issue on the negotiating agenda. This began to change 2 years ago, at the Glasgow Climate Conference (COP 26), when negotiators took an important—though long overdue—step by calling for the “phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, while providing targeted support to the poorest and most vulnerable in line with national circumstances and recognizing the need for support towards a just transition” (p. 5). The same call was repeated a year later at COP 27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt.

While these calls are a clear sign that negotiators see addressing fossil fuel subsidies as important for climate action, the commitment is flawed in that it (i) lacks a clear deadline, (ii) uses an undefined qualifier (“inefficient”) that allows countries to argue that they have no fossil fuel subsidies, and (iii) does not provide for a follow-up process to track progress.

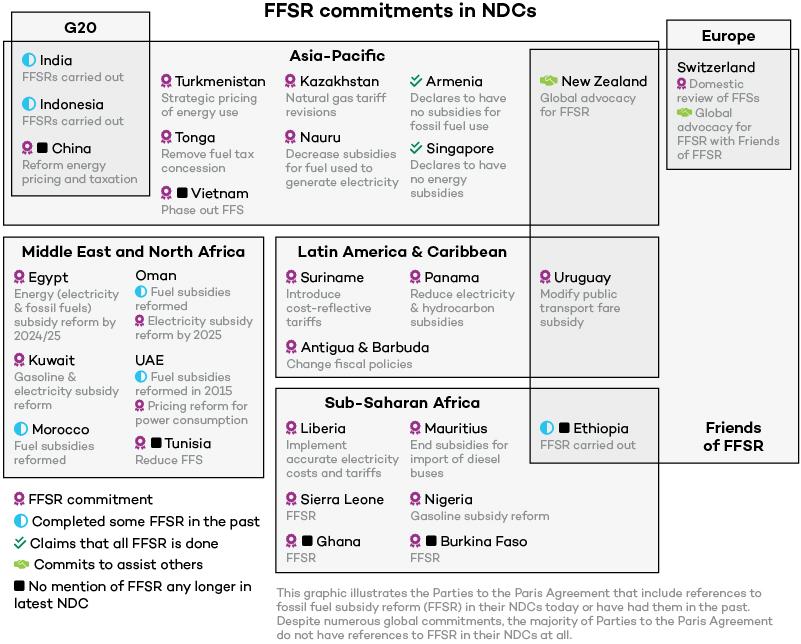

In addition to this global commitment, some countries have referred to fossil fuel subsidies in their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) submitted under the Paris Agreement. This is important because including fossil fuel subsidy reform in NDCs may make it harder for political leaders to backslide and for future governments to reverse reforms, as domestic stakeholders can hold their governments to account.

However, a closer look at these references reveals several weaknesses. First, so far only 29 out of 198 parties have included some form of reference to fossil fuel subsidies in one of their NDCs. Second, as of the latest generation of new or updated NDCs, only 16 parties have included an actual commitment to reform their subsidies. Two parties (Armenia and Singapore) use their NDCs to argue that they have no subsidies whatsoever (notwithstanding data suggesting otherwise). Four parties (including India and Indonesia) mention that reforms have been carried out in the past. And another party (New Zealand) only includes a commitment to help other countries with reforming subsidies. Third, six countries (Burkina Faso, China, Ethiopia, Ghana, Tunisia, Vietnam) that included a reference to some kind of fossil fuel subsidy reform in their initial NDC submitted at the time of the adoption of the Paris Agreement omitted this in their new or updated NDC submitted a few years later.

The 16 countries that committed to reform their fossil fuel subsidies include some of 2022’s big subsidizers, such as Egypt (USD 28 billion), Kazakhstan (USD 18 billion), Nigeria (USD 5 billion), and Turkmenistan (USD 4 billion). However, most countries that commit to reform are low-income and small economies that do not provide a large volume of fossil fuel subsidies. Strikingly, there are no G7 countries among them (even though the G7 committed to phasing out subsidies by 2025), nor do they include any G20 countries. Likewise, the European Union’s (EU’s) NDC is silent about fossil fuel subsidies, even though the bloc has pledged to phase out fossil fuel subsidies domestically.

How Parties Should Strengthen Global Commitments on Fossil Fuel Subsidies at COP 28

At COP 28 and in its immediate aftermath, Parties have numerous opportunities to address the identified weaknesses. They can start doing so in Dubai by strengthening the commitment made in Glasgow and Sharm el-Sheikh. This process would include

- setting a clear deadline—e.g., 2025 for developed countries, following the G7’s example, and 2030 for developing countries.

- removing or clarifying the term “inefficient,” which does not have an internationally agreed definition. A better approach would be to instead name exceptional cases when subsidies could be considered justifiable. For example, the EU is calling for the removal of fossil fuel subsidies “which do not address energy poverty or just transition.”

- mandating a follow-up process—e.g., requesting that the UNFCCC Secretariat develop a report on fossil fuel subsidies and climate change.

- expanding the commitment to address all public financial flows, including domestic and international public finance, and investment through state-owned enterprises. G20 countries provided at least USD 372 billion in such finance to fossil fuels in 2022.

One way of achieving this at COP 28 would be to adopt a so-called “cover decision” similar to the Glasgow Climate Pact. However, given that cover decisions are the product of negotiations on the official UNFCCC agenda, their adoption is not a given, and more far-reaching cover decisions are likely to encounter more resistance from Parties.

A global commitment to reform fossil fuel subsidies by a given date could also be part of the outcomes of the first global stocktake, which is due to wrap up at COP 28. In the global stocktake’s technical dialogues, various Parties and non-Party stakeholders have drawn attention to the potential of phasing out fossil fuel subsidies for climate change mitigation. As a consequence, a synthesis report by the UNFCCC Secretariat summarizing these submissions included concrete suggestions on how fossil fuel subsidy reform may feature in the outcome of the process. This means that if countries fail to adopt a cover decision, there is still a clear opportunity for Parties to include a commitment to address fossil fuel subsidies as part of a possible COP decision resulting from the global stocktake. Although the precise outcomes of the global stocktake are as yet undetermined at this stage, they could include a COP decision along with a technical annex, which could specify details.

How Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform Should Feature in New National Commitments and Enhanced Transparency

Following the global stocktake, Parties are expected to develop and submit new—and more ambitious—NDCs. These offer space for governments to include national commitments on reforming or removing fossil fuel subsidies, drawing on—and, where possible, improving—existing practices. These contributions could include, for example, time-bound reform commitments or pledges to phase out specific subsidies. The spotlight should be, in particular, on those countries that have committed to subsidy reform in other forums (notably the G7, G20, and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation countries), as well as countries that have advocated for reform (including countries that belong to the Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform).

What’s more, it will be important that the references to fossil fuel subsidies are forward-looking, including actions to be taken by countries, rather than reflecting on past developments. Civil society will play an important role in providing support for countries to include fossil fuel subsidy reform in their NDCs, as well as accountability for countries that have already committed to doing so. International organizations, such as the World Bank and United Nations Development Programme, will play a similarly important part in assisting countries in including subsidy reform commitments in their NDCs.

To the extent that countries include fossil fuel subsidy reform commitments in their NDCs, there is also an opportunity to strengthen transparency through the UNFCCC. Parties are required to submit biennial reports on the progress made in implementing and achieving NDCs. These reports are reviewed by technical experts, as well as through a facilitative, political peer-review process. Importantly, however, Parties can choose the indicators they will report on. For the reporting and review process to be meaningful, it will be crucial that Parties with commitments choose fossil fuel subsidy-related indicators (e.g. indicators related to SDG 12.c) and report on those. Countries should also be encouraged to submit the data on the fossil fuel subsidies they have reported in the context of the SDGs.

How Fossil Fuel Subsidies Can Be Addressed Through Discussions on Climate Finance

Another place where fossil fuel subsidies can be—and have been—discussed is under talks on climate finance, particularly those related to Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement. At COP 27, Parties established the Sharm el-Sheikh dialogue on the scope of Article 2.1(c), which held two workshops in 2023. Fossil fuel subsidies have not been specifically discussed in this dialogue, although the EU has suggested doing so in future.

Also related to Article 2.1(c) is the work by the Standing Committee on Finance (SCF), which has included information from third-party sources (e.g., the Fossil Fuel Subsidy Tracker) on fossil fuel subsidies as part of its Fifth Biennial Assessment and Overview of Climate Finance Flows. In addition, the SCF has been collecting views on how to achieve Article 2.1(c). In response, various Parties and non-Party stakeholders have called for action on fossil fuel subsidies, including both a general phase-out commitment and follow-up action (e.g., an annual progress report). However, some Parties have also expressed reservations about considering fossil fuel subsidies in the context of Article 2.1(c). COP 28 is expected to include discussions on Article 2.1(c), and these could potentially result in a decision on a further dialogue or work program in which fossil fuel subsidies could feature as a topic.

Moreover, discussions on the UNFCCC’s “new collective quantified goal on climate finance” (NCQG)—which requires developed countries to provide developing countries with climate finance to support the implementation of the Paris Agreement—have included fossil fuel subsidies. One of the purposes of these talks is to negotiate a new goal that would follow the USD 100 billion annual climate finance goal from 2025 onwards. In addition to the new “quantity” (i.e., how much climate finance ought to be provided), Parties have begun to discuss the “quality” of climate finance. For instance, the Association of Latin America and the Caribbean has suggested a concept of “net climate finance,” where the value of climate finance would be reduced by finance provided to high-emissions activities, including fossil fuel subsidies. Some Parties have also suggested that fossil fuel subsidy reform may be used as an innovative source of financing, which could help achieve the NCQG. Discussions on the NCQG are expected to wrap up at COP 29 in 2024, and it remains to be seen how fossil fuel subsidies will feature in the final goal.

How Countries Can Create a Dialogue on Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform in the Mitigation and Just Transition Work Programs

Fossil fuel subsidies may feature in two recently established work programs. First, COP 27 established a work program on just transition pathways, which may address fossil fuel subsidies as part of its work. However, at this stage, Parties still have to agree on the objectives, scope, and modalities of the work program. Similarly, Parties in Sharm el-Sheikh launched a new Sharm el-Sheikh mitigation ambition and implementation work program to scale up mitigation action in the short term. In the first “global dialogue” of this work program, participants highlighted fossil fuel subsidy reform as a mitigation action. Although the outcomes of these work programs remain to be determined, they provide an opportunity for countries to share experiences on fossil fuel subsidy reform.

The Time for Action on Fossil Fuel Subsidies is Now

Parties have plenty of options to make progress on fossil fuel subsidy reform at and after COP 28. What we need now is the political will. Fossil fuel subsidy reform is essential to an effective global response to the climate crisis. Countries must take the opportunity to make progress on this agenda at COP 28 and beyond.

Harro van Asselt is Hatton Professor of Climate Law, Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge and Jakob Skovgaard is Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, Lund University, Sweden.

You might also be interested in

Blackouts and Backsliding: Energy subsidies in South Africa 2023

Blackouts and Backsliding presents the latest energy subsidy data for South Africa.

South African Fossil Fuel Subsidies Hit Record Highs as Country's Energy Crisis Deepens

South Africa's fossil fuel subsidies tripled between 2018 and 2023, hitting USD 7.5 billion, up from USD 2.9 billion 5 years earlier, a new report by IISD reveals.

IISD: EU’s historic Energy Charter Treaty vote will boost energy transition

The European Parliament has voted for the European Union to withdraw from the climate-threatening Energy Charter Treaty.

G20 Finance Ministerials and World Bank/IMF Spring Meetings: Expert comment

G20 finance ministerials and World Bank/IMF spring meetings will take place this week in Washington. High on the agenda is the need to mobilize trillions of dollars of investment in the transition to clean energy.